When pop-up COVID-19 testing sites opened all over Chicago and cities across the U.S. late last year, many had the same question on their minds: Where did they all come from, and who was authorizing them?

A few Chicago-area companies were responsible for managing tens of thousands of tests and hundreds of individual testing sites nationwide.

Many of these testing locations were housed in business spaces shuttered during the pandemic.

And it turns out, many of the locations received little scrutiny from regulators before opening their doors.

That is, until the complaints began pouring in.

Questions over how these local testing operations and affiliated labs operated, along with their testing accuracy and reliability, swirled during the Omicron infection wave, leading to lawsuits, and investigations into some company practices.

While the federal and state investigations are ongoing, many testing companies have since closed.

Now, one thing is clear: those operations were paid for by taxpayers, and received millions of dollars in federal reimbursements earmarked specifically for testing the uninsured.

Access to those funds was granted, in part, due to testing companies partnering with federally-certified labs.

Early on, when pop-up COVID testing sites appeared seemingly overnight, health officials advised the public that these locations were not regulated, and that the only real way to find out if a company was reliable was to verify if the company’s testing lab was certified by federal regulators.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

But now, some experts are questioning that certification process, calling it ‘too easy’ with ‘little scrutiny’, and saying Congress should get involved to write new laws that would modernize the way that labs are approved to conduct clinical testing, like COVID PCR testing, as well as mandatory follow-up inspections before problems arise.

As of now, there are blind spots in the system of oversight meant to ensure laboratories perform safe and reliable medical testing, according to experts in the field.

“It's relatively easy to fill out a form and to say, ‘Yes, I'm going to follow the regulations,’” said Stephen Master, MD, PhD.

Master is the President of the American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC), an organization made up of scientists and medical professionals that focus on clinical laboratory procedures, and its application to healthcare.

Master says the COVID-19 testing problems with some Chicago-area companies and labs does not reflect widespread issues within the industry, but stricter certification and inspection standards may have prevented some of the issues brought to light during the pandemic.

“There's a difference between established laboratory groups and new, pop-up labs during something like COVID, and we need some sort of mechanism for making sure that groups that are entering the field like that understand what their responsibilities are,” Master said.

Master continued, “I think that's what sort of got us into this position because anyone can fill out a form and then not follow the law.”

Center for COVID Control

There was the sprawling 6,800 square foot mansion on nearly four acres of pristine Saint Charles land worth $1.36 million.

There were also two Lamborghinis, a Tesla Model Y and a Ferrari Enzo; designer cars totaling millions of dollars.

These aren’t lottery winnings, rather they are the purchases made by the husband and wife co-owners of Center for COVID Control (CCC), a COVID testing company based in the Chicago suburbs that operated hundreds of testing sites across the country.

Those purchases were allegedly paid for by taxpayers, one COVID test at a time, according to a lawsuit filed by the Oregon State Attorney General’s office.

The Oregon AG’s office sued CCC this past April, saying it was “deceptively marketing testing services and for violating the state’s Unlawful Trade Practices Act.”

The lawsuit alleges that the COVID tests and results it processed for thousands of people were riddled with inaccuracies.

In addition to the Oregon lawsuit, the company is under investigation by many other state and federal agencies as well.

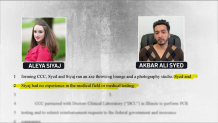

CCC’s owners, Ali Syed and Aleya Siyaj, stand accused by the Oregon AG of funneling “millions of dollars… for testing, to [themselves].”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows CCC billed many of those tests on the federal government’s tab, totaling more than $152 million.

Neither Syed nor Siyaj responded to NBC 5’s request for comment for this report, but in the past have denied any wrongdoing. The couple attributed problems to the sudden surge of testing needs across the country.

NBC 5 Responds has been reporting on CCC since the start of the year, including how the company was able to expand across the country so quickly and become one of the largest COVID testing providers nationwide.

Yet, the Oregon AG’s office alleges the owners built this COVID testing empire with no medical or testing experience.

“Prior to forming CCC, Syed and Siyaj ran an axe throwing lounge and a photography studio. Syed and Siyaj had no experience in the medical field or medical testing,” the lawsuit alleges.

Instead, Oregon investigators found CCC’s owners partnered with, and acquired ownership of, a federally-certified lab, Doctors Clinical Laboratory (DCL) in Rolling Meadows that “performed PCR testing and submitted reimbursement requests to the federal government and insurance companies.”

This despite the fact that the lab didn’t have the staffing, capacity or ability to perform the tens of thousands of tests it was receiving each day.

After many complaints, regulators with the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) performed an inspection of DCL and found failure after failure, according to a December inspection report reviewed by NBC 5 Responds.

Inspectors found many deficiencies including test samples that “were not labeled with either a patient name or unique identifier," tests not stored at proper temperatures, and some tests conducted “too early or too late” for best results.

The CMS report also noted an 11-day stretch in November 2021 when the lab collected more than 84,000 swabs but failed to test nearly half of them within the required time frame due to storage problems.

But inspectors didn’t step foot into DCL until after complaints were filed, rather than before the problems started, and that could be a blind-spot for regulators and the public that relies on medical tests.

'Not Routinely Inspected'

Medical testing labs in the U.S. are required to have what’s referred to as “CLIA certification” from state and federal regulators.

“CLIA” refers to an amendment made by Congress back in 1988 to the Public Health Services Act that created “federal standards applicable to all U.S. facilities or sites that test human specimens for health assessment or to diagnose, prevent, or treat disease,” according to the CDC.

But Dr. Master says there have been shockingly little updates or improvements to those guidelines since the amendment was passed decades ago.

“It's been decades, and we really need to rethink what CLIA needs to be,” Master said, adding that with people relying on the results by these labs and its laboratory director, regulators “need to make sure that someone knows what they're doing.”

CLIA certification can also unlock a lab’s access to federal funds, as well as partnerships with state and local organizations.

But it doesn’t trigger any immediate inspections or visits by regulators.

NBC 5 Responds found in the state of Illinois, once a lab is certified by the Public Health Department, it is “not routinely inspected” unless a complaint is filed, according to IDPH’s lab certification guidelines obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by NBC 5.

Meaning in most cases, labs are only inspected after problems arise, rather than before.

In fact, Dr. Master said it can be months, if not up to a year, before any regulators step foot inside a clinical lab.

“Once someone gets that CLIA certificate… there's a gap period before they get inspected,” Master said, adding that regulators “need to make sure that someone [running a lab] knows what they are doing.”

Other Chicago-Area Labs Under Investigation

That’s not what happened with three Chicago-based COVID testing labs: CCC, and two other local labs that were not named in the Oregon lawsuit, O’Hare Clinical Laboratory and Northshore Clinical Laboratory.

All three labs were responsible for an untold number of COVID tests nationwide last year, as well as a host of deficiencies discovered by regulators.

Certification records from IDPH officials show all three labs had received CLIA certification.

Each lab billed taxpayers for millions of dollars in COVID-19 testing.

Northshore Clinical Laboratory received $164.8 million.

O’Hare Clinical Laboratory received $187.1 million.

After a mountain of public complaints surfaced late-2021, CMS regulators inspected both Northshore and O’Hare and found a long list of deficiencies in each lab, according to inspection reports reviewed by NBC 5.

O’Hare Clinical Laboratory did not respond to NBC 5’s questions for this report, but previously attributed challenges to the rise in infections, noting that it provided a vital service for the community at a time when testing resources were limited.

In the case of Northshore Clinical Laboratory, one of the many deficiencies CMS inspectors discovered in December 2021 was that the laboratory’s director was “not qualified” to perform “high-complexity testing”, such as COVID PCR tests.

This, despite the fact that the director had been previously approved during the CLIA-certification process by inspectors with the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Internal guidelines from IDPH show that its employees are “responsible for verifying the [Lab] Director meets the appropriate personnel qualifications.”

When asked why IDPH approved Northshore’s director for this type of testing, despite the director not having the legal qualifications to do so, an IDPH spokesperson referred all questions to CMS.

CMS confirmed to NBC 5 that Northshore’s lab director had been certified by state inspectors from 2006 to 2021, despite not having the legally required qualifications, but that upon this discovery during the December inspection, Northshore was immediately dealt with.

“Immediate action was taken to cite the deficient practice for lack of a qualified high-complexity laboratory director,” a spokesperson for CMS said, adding that Northshore quickly named a new, legally qualified director months after it was cited.

A spokesperson for Northshore Clinical Laboratory did not answer specific questions from NBC 5, but said it addressed “the cited deficiencies” from the December inspection, and that “Northshore is continuing to work with CMS and IDPH to address their concerns.”

When asked about the need for ‘routine inspections,’ a spokesperson for CMS said it “continues to evaluate the oversight of [testing] labs”

Dr. Master believes the pandemic taught the medical testing community many lessons, and one of those lessons is the need for Congress to review the certification process for testing labs.

“CLIA modernization should be something that's discussed at a congressional level because they would have the statutory authority to actually implement those stronger measures,” Master said.