Chicago's top doctor said the question of whether or not the omicron variant will mark the end of the coronavirus pandemic isn't quite as cut and dry as many would like it to be.

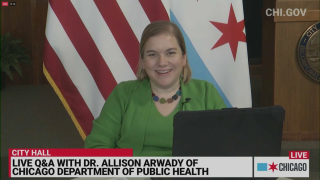

While some have questioned whether the highly-transmissible omicron variant could signal a sign that future COVID variants will become less severe or signal the end of the pandemic, Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Dr. Allison Arwady said there are a number of possibilities for the future of the virus.

"The short answer to that is - and the honest answer to that is - I do not know for sure what is going to 'happen next after omicron' and neither does anybody else in the world," Arwady said during a Facebook Live Thursday. "There are a lot of hypotheses that range from a best case scenario - best-case scenario would say this has been enough of a spread that we'll have enough people who have had protection and that protection will be more long lasting. I don't think there's anybody in the world really who looks at this closely who thinks this will be the last variant. In a best most rosy-case scenario, future variants would be less virulent, less likely to make people sick, ideally less infectious, etc."

That could be the case, she said. But what happens next could also be very different.

"There is nothing that says a future variant could not also be more virulent, make people sick, or not, you know, in a worst case scenario, not protect against those severe outcomes. I certainly hope that is not what is going to happen but it would be irresponsible to say that is not in you know in the range," she said. "So we have sort of a best case and worst case scenario."

Her comments echo those made by White House Chief Medical Adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci earlier this week.

"It is an open question whether it will be the live virus vaccination that everyone is hoping for," Fauci said via videoconference at The Davos Agenda virtual event.

"I would hope that that's the case. But that would only be the case if we don't get another variant that eludes the immune response of the prior variant," he added.

Arwady said she feels confident that the U.S. will "be in a pretty good place, you know, for a few month" after the omicron surge subsides, but she noted that the virus is not as predictable as influenza, for example.

"COVID has not followed a seasonal pattern clearly at this point in the way influenza does," she said. "Really every three months we've been seeing surges. Nobody expected to see a delta surge across the summer in the U.S., for example. So I expect, as we've seen with prior surges, as we sort of come down, there will be a period of relative control and yes, we will move to be lifting restrictions and you know, taking advantage of that. In a best case scenario, things would stay in very good control, but it is way too early to call that."

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

Arwady said earlier this week that the delta variant "has been what we call out competed by omicron."

"Meaning that because omicron is so much more infectious, so much more contagious, that it has had the opportunity to spread very, very quickly and we see it sort of replaced delta," she said Tuesday.

As of Wednesday, just 0.7% of the city's cases were believed to be caused by the delta variant.

"You can see 99.3% is the estimate of all of the COVID cases are the omicron variant and just 0.7% are delta and nothing else is showing up at this point," she said.

Arwady added that additional variants are possible going forward - and other health experts agree.

Getting progressively better at evading immunity helps a virus to survive over the long term. When SARS-CoV-2 first struck, no one was immune. But infections and vaccines have conferred at least some immunity to much of the world, so the virus must adapt.

"The faster omicron spreads, the more opportunities there are for mutation, potentially leading to more variants,” Leonardo Martinez, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Boston University, said.

When new variants do develop, scientists said it’s still very difficult to know from genetic features which ones might take off. For example, omicron has many more mutations than previous variants, around 30 in the spike protein that lets it attach to human cells. But the so-called IHU variant identified in France and being monitored by the WHO has 46 mutations and doesn’t seem to have spread much at all.

"Should we be worried about a new variant? I don't think we're done with variants," Arwady said. "My money would not be on that we would see a new, very concerning variant very soon, just because omicron has been so contagious and infectious and has out competed delta and others so fast, but omicron came really quickly, too."

What will happen next, remains to be seen.

"There are doomsday options out there, there are extremely positive... I think we'll probably be somewhere in the middle there," Arwady said. "And we will learn a lot more as we see, as we come out of this omicron surge."