- The bird flu outbreak took several concerning turns this year, with the number of human cases up to at least 64.

- Experts outlined several indicators that the virus’ spread is going in the wrong direction.

- Among them are recent detections of the virus in wastewater and signs of dangerous mutations.

The simmering threat of bird flu may be inching closer to boiling over.

This year has been marked by a series of concerning developments in the virus’ spread. Since April, at least 64 people have tested positive for the virus — the first U.S. cases other than a single infection in 2022. Dairy cow herds in 16 states have been infected this year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the country’s first severe bird flu infection on Wednesday, a critically ill patient in Louisiana. And California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency this week in response to rampant outbreaks in cows and poultry.

“The traffic light is changing from green to amber,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies infectious diseases. “So many signs are going in the wrong direction.”

No bird flu transmission between humans has been documented, and the CDC maintains that the immediate risk to public health is low. But scientists are increasingly worried, based on four key signals.

For one, the bird flu virus — known as H5N1 — has spread uncontrolled in animals, including cows frequently in contact with people. Additionally, detections in wastewater show the virus is leaving a wide-ranging imprint, and not just in farm animals.

Then there are several cases in humans where no source of infection has been identified, as well as research about the pathogen’s evolution, which has shown that the virus is evolving to better fit human receptors and that it will take fewer mutations to spread among people.

Health

Together, experts say, these indicators suggest the virus has taken steps toward becoming the next pandemic.

“We’re in a very precarious situation right now,” said Scott Hensley, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly> Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

Widespread circulation creates new pathways to people

Since this avian flu outbreak began in 2022, the virus has become widespread in wild birds, commercial poultry and wild mammals like sea lions, foxes and black bears. More than 125 million poultry birds have died of infections or been culled in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

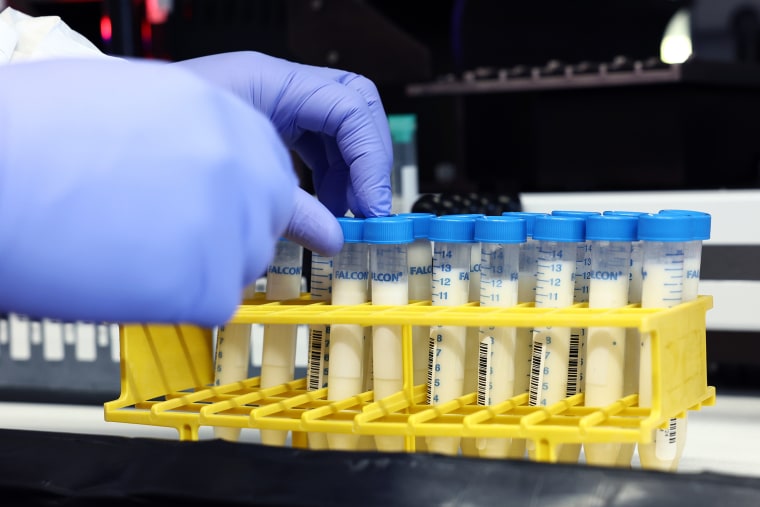

An unwelcome surprise arrived in March, when dairy cows began to fall ill, eat less feed and produce discolored milk.

Research showed the virus was spreading rapidly and efficiently between cows, likely through raw milk, since infected cows shed large amounts of the virus through their mammary glands. Raccoons and farm cats appeared to get sick by drinking raw milk, too.

The more animals get infected, the higher the chances of exposure for the humans who interact with them.

“The more people infected, the more possibility mutations could occur,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, a professor of epidemiology and the director of the Brown University School of Public Health’s Pandemic Center. “I don’t like giving the virus a runway to a pandemic.”

Until this year, cows hadn’t been a focus of influenza prevention efforts.

“We didn’t think dairy cattle were a host for flu, at least a meaningful host,” Andrew Bowman, a professor of veterinary preventive medicine at Ohio State University, told NBC News this summer.

But now, the virus has been detected in at least 865 herds of cows across at least 16 states, as well as in raw (unpasteurized) milk sold in California and in domestic cats who drank raw milk.

“The ways in which a community and consumers are directly at risk now is in raw milk and cheese products,” Chin-Hong said. “A year ago, or even a few months ago, that risk was lower.”

Cases with no known source of exposure

The majority of the human H5N1 infections have been among poultry and dairy farmworkers. But in several puzzling cases, no source of infection has been identified.

The first was a hospitalized patient in Missouri who tested positive in August and recovered. Another was a California child whose infection was reported in November.

Additionally, Delaware health officials reported a case of H5N1 this week in a person without known exposure to poultry or cattle. But CDC testing could not confirm the virus was bird flu, so the agency considers it a “probable” case.

In Canada, a British Columbia teenager was hospitalized in early November after contracting H5N1 without any known exposure to farm or wild animals. The virus’ genetic material suggested it was similar to a strain circulating in waterfowl and poultry.

Such unexplained cases are giving some experts pause.

“That suggests this virus may be far more out there and more people might be exposed to it than we previously thought,” Nuzzo said.

Rising levels of bird flu in wastewater

To better understand the geography of bird flu’s spread, scientists are monitoring wastewater for fragments of the virus.

“We’ve seen detections in a lot more places, and we’ve seen a lot more frequent detections” in recent months, said Amy Lockwood, the public health partnerships lead at Verily, a company that provides wastewater testing services to the CDC and a program called WastewaterSCAN.

Earlier this month, about 19% of the sites in the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System — across at least 10 states — reported positive detections.

It’s not possible to know if the virus fragments found came from animal or human sources. Some could have come from wild bird excrement that enters storm drains, for example.

“We don’t think any of this is an indication of human-to-human transmission now, but there is a lot of H5 virus out there,” said Peggy Honein, the director of the Division of Infectious Disease Readiness & Innovation at the CDC.

Lockwood and Honein said the wastewater detections have mostly been in places where dairy is processed or near poultry operations, but in recent months, mysterious hot spots have popped up in areas without such agricultural facilities.

“We are starting to see it in more and more places where we don’t know what the source might be automatically,” Lockwood said, adding: “We are in the throes of a very big numbers game.”

One mutation away?

Until recently, scientists who study viral evolution thought H5N1 would need a handful of mutations to spread readily between humans.

But research published in the journal Science this month found that the version of the virus circulating in cows could bind to human receptors after a single mutation. (The researchers were only studying proteins in the virus, not the full, infectious virus.)

“We don’t want to assume that because of this finding that a pandemic is likely to happen. We only want to make the point that the risk is increased as a result of this,” said paper co-author Jim Paulson, the chair of molecular medicine at Scripps Research.

Separately, scientists in recent months have identified concerning elements in another version of the virus, which was found in the Canadian teenager who got seriously ill. Virus samples showed evidence of mutations that could make it more amenable to spreading between people, Hensley said.

A CDC spokesperson said it’s unlikely the virus had those mutations when the teen was exposed.

“It is most likely that the mixture of changes in this virus occurred after prolonged infection of the patient,” the spokesperson said.

The agency’s investigations do not suggest that “the virus is adapting to readily transmit between humans,” the spokesperson added.

The viral strain in the United States’ first severe bird flu case, announced on Wednesday, was from the same lineage as the Canadian teen’s infection.

Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said the CDC is assessing a sample from that patient to determine if it has any concerning mutations.

Hensley, meanwhile, said he’s concerned that flu season could offer the virus a shortcut to evolution. If someone gets co-infected with a seasonal flu virus and bird flu, the two can exchange chunks of genetic code.

“There’s no need for mutation — the genes just swap,” Hensley said, adding that he hopes farmworkers get flu shots to limit such opportunities.

Future testing and vaccines

Experts said plenty can be done to better track bird flu’s spread and prepare for a potential pandemic. Some of that work has already begun.

The USDA on Tuesday expanded bulk testing of milk to a total of 13 states, representing about 50% of the nation’s supply.

Nuzzo said that effort can’t ramp up soon enough.

“We have taken way too long to implement widespread bulk milk testing. That’s the way we’re finding most outbreaks on farms,” she said.

At the same time, Andrew Trister, chief medical and scientific officer at Verily, said the company is working to improve its wastewater analysis in the hope of identifying concerning mutations.

The USDA has also authorized field trials to vaccinate cows against H5N1. Hensley said his laboratory has tested a new mRNA vaccine in calves.

For humans, the federal government has two bird flu vaccines stockpiled, though they would need Food and Drug Administration authorization.

Nuzzo said health officials should offer the vaccines to farmworkers.

“We should not wait for farmworkers to die before we act,” she said.

Additionally, scientists are developing new mRNA vaccines against H5N1. This type of vaccine, which was first used against Covid-19, can be more quickly tailored to particular viral strains and also scaled more quickly.

Hensley’s lab in May reported that one mRNA vaccine candidate offered protection against the virus to ferrets during preclinical testing. Another candidate under development by the CDC and Moderna has also showed promising results in ferrets, which are often used as a model for humans to study influenza.

“Now we just have to go through the clinical trials,” Hensley said.

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com. More from NBC News: