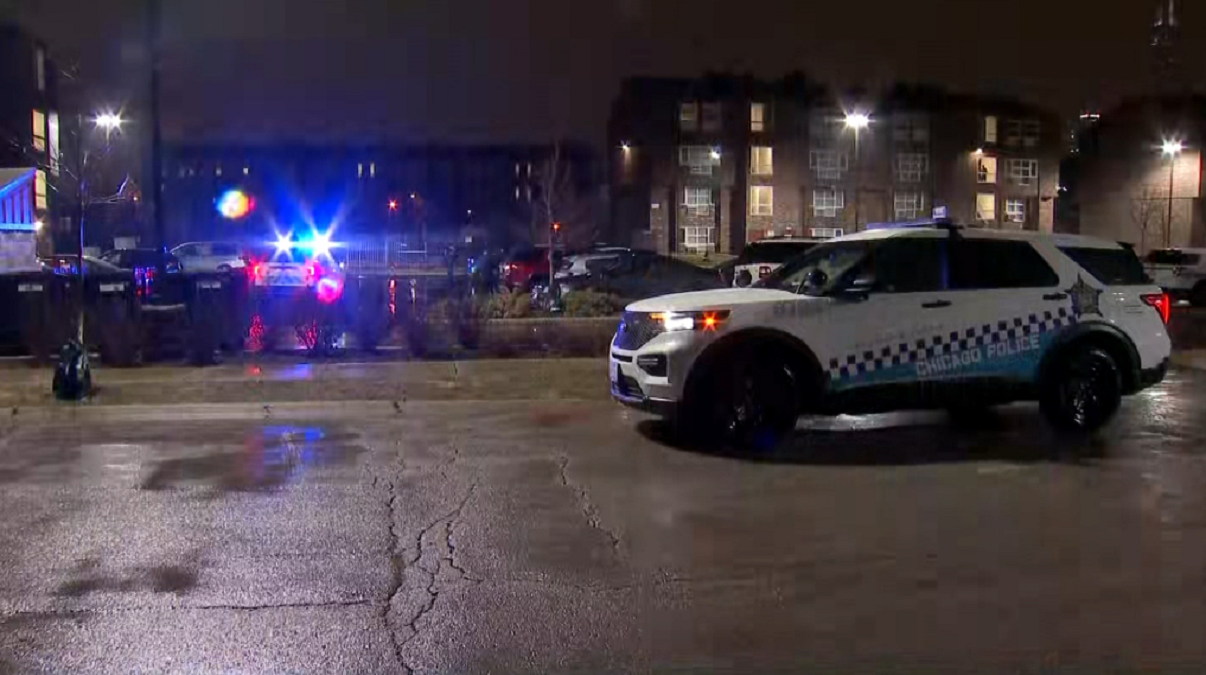

Outside the Chicago Police Department’s 1st District, extension cords run across the rain-soaked sidewalk and in between tents.

Mattresses are pressed up against the police station as a small group of people played dominoes.

There’s a mix of optimism and uncertainty. People who’ve left their home country – for many, that’s Venezuela – have come to Chicago seeking a better life.

But it’s unclear where they will end up.

The number of migrants living at temporary shelters set up at Chicago police stations has ballooned to more than 2,500 people, according to the city’s count, part of the 17,000-plus who now call Chicago home. Their stays at police stations are supposed to be temporary – but some of the people said they have been living at such buildings since August.

Colder days are ahead, and it’s not clear when the winterized tents the city promised will be up and running, or where they’ll be located.

One woman said that she has medical needs, but is concerned about leaving the police station out of fear she could lose her place here.

Local

NBC 5 Investigates wanted to know more about the migrants’ experiences and their medical needs after a volunteer group – the Migrant Mobile Health Team – testified before Chicago's City Council last week about issues they’re seeing.

The group, created with the help of University of Illinois Chicago second-year medical student Sara Izquierdo, said they are filling a gap in medical care created in part by the city’s response to the crisis. Izquierdo told council members that her group has crowdsourced to raise money, and without city tax money has helped provide medical care and assessments to the migrants living at police stations.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly> Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

Her group has grown to more than 250 volunteers since May. Medical students like Sara and doctors volunteer their time to help treat migrants living at the city’s police stations.

“All of these volunteer organizations have truly just saw the need and filled the need. There's really no other way to put it,” said Sara Cooper, a UIC medical student and native of Venezuela who volunteers with the group.

Cooper says she and her colleagues have treated barbed-wire wounds and helped women who have had no pre-natal care.

And there is a widening gap – Cooper and Izquierdo say – created by the city’s response.

“We need collaboration from the city,” Izquierdo told council members last Friday.

During her testimony at a committee hearing, Sara Izquierdo was critical of the city’s spending.

NBC 5 Investigates found the city has at least $57 million so far on Favorite Healthcare Staffing – a Kansas-based company that staffs the city-run shelters.

An invoice from last December shows the company billed the city $20,000 for a single nurse’s invoice for one week.

“There's no reason that one nurse working for seven days should get paid $20,000 when you could take that $20,000 and install a triage system like ours saves people's lives. There's no reason for that,” Izquierdo said. “There's no reason that we should be spending the money on 400 ambulances, when people are coming for concerns for diarrhea, sore throat, things that can be managed otherwise, and a better way, but aren't managed at all.”

The mayor’s office has said those hourly rates were inflated to cover administrative costs like hotel rooms for out-of-state employees and that it is now working with Favorite, encouraging the company to hire more locally.

“We're not talking about creative solutions. We're just talking about paying large corporations and large companies like GardaWorld inordinate amounts of money to put more band-aid solutions on things,” Izquierdo said.

The $29 million contract with GardaWorld is aimed at moving people out of police stations, but where the so-called tent cities will go up is still unclear.

The volunteers with the Migrant Mobile Health Team said they met Thursday with the Chicago Department of Public Health to discuss needs.

A spokesperson for the Chicago Police Department referred questions to Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office. The mayor's office had not responded to an email seeking comment as of Friday afternoon.

A spokesperson released the following statement on behalf of Mayor Brandon Johnson's office, the Chicago Department of Public Health and the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services:

"The City of Chicago is coordinating with various providers to try to ensure that new arrivals undergo health screenings and have access to healthcare as needed. New arrivals receive health screenings and have access to medical care via a clinic operated by Cook County Health.

The Chicago Department of Public Health provides complimentary support by funding onsite clinical providers in new arrival shelters and by coordinating Medical Reserve Corps volunteers to perform screenings in Chicago Police Department districts so that new arrivals can be connected to care. Separate from clinical care, the Chicago Department of Public Health has a dedicated team that provides infection control consultation to congregate settings, including Department of Family and Support Services-run shelters."

(Update: an earlier version of this story misidentified the Chicago Department of Public Health as the Cook County Health Department. It is corrected above).