It's a sisterhood born of pain that no one wants to be a part of.

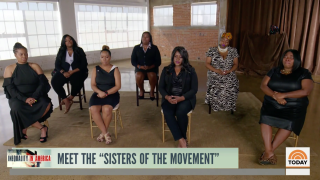

Seven women who are siblings of six Black men and women who were killed by police or died in police custody have come together to make a change.

The women, who call themselves "Sisters of the Movement," all met for the first time as they spoke to Morgan Radford on TODAY Thursday about President Donald Trump's recent executive order on police reforms and the changes they are demanding to policing in America.

"Our main focus is change — changing the laws, changing policing, in general, because we know that pain," Allisa Findley said.

"I live it every day. They live it every day. And we don't want anyone else to go through that."

Findley's brother was Botham Jean, who in 2018 was shot and killed in his home by a former Dallas police officer who accidentally entered the wrong apartment and mistook the 26-year-old accountant for an intruder.

U.S. & World

She is joined in the sisterhood by Shante Needham, the sister of Sandra Bland, 28, who was found hanged in a Texas jail cell in 2015, three days after being arrested at a traffic stop.

Tiffany Crutcher is the twin sister of Terence Crutcher, 40, who was shot and killed by police next to his vehicle in 2016 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Natasha Duncan is the sister of Shantel Davis, 23, who was fatally shot in 2012 after being pulled over by a New York City police detective in Brooklyn.

Victoria Davis is the sister of Delrawn Small, 37, who was fatally shot in front of his wife and 4-month-old son by an NYPD officer in 2016. Ashley and Amber Carr are the sisters of Atatiana Jefferson, 28, who was shot and killed by a police officer in her home in Forth Worth, Texas, while her sisters say she was playing video games with Amber Carr's son.

In every case, the victims were unarmed.

Only former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison last year for killing Botham, has been convicted. The officers in the other five cases were either found not guilty, are awaiting trial, or are no longer under investigation.

"That's a scary place to live in, to know that at any time, my life can be taken from me," Ashley Carr said. "I'm trying to do things to better ourselves and better our communities, and we still are looked at as easy prey, easy targets."

The women are seeking changes in policing that involves five crucial steps:

- Federal legislation changing the "use of force" standard/continuum.

- Mandatory independent investigations of police use-of-force incidents resulting in death or injury and in-custody deaths.

- Abolishment of qualified immunity for police officers that protects them from lawsuits.

- Increased oversight of federal money to state and local police departments.

- Mandatory independent psychological evaluation when people apply for jobs with the police, and follow-up psychological evaluations throughout the officer's career.

The executive order on policing signed by Trump on Tuesday encourages police departments to meet standards like a ban on chokeholds unless an officer's life is at risk. The order also aims to create a national database of excessive force complaints. The president signed it after meeting privately with eight families whose loved ones were killed by police.

Activists, lawmakers and family members of those killed by police said that the order doesn't mandate any important change.

One of the families who met with Trump told Radford the group refused a photo-op with the president because the executive order was missing a zero-tolerance policy for officers with previous infractions and had no provision for a federal investigation of police brutality.

The executive order comes amid ongoing protests about police brutality and racial injustice following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody last month. The names of many of the siblings of the seven women have been rallying cries at numerous protests.

Watching the video of officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly nine minutes brought back painful memories for the seven women, some of whom said they saw videos of their loved ones being killed.

"I saw Terence lying on the ground with blood everywhere," Crutcher said. "I have not been able to get that image out of my head, of my twin laying on that ground, like roadkill."

"I didn't watch George Floyd's video because I heard that he had cried out for his mom," Davis said. "The thought of a grown man crying out for his mom bothered me. Because then I started to kind of obsess over, like, did Delrawn cry out for our mom?"

The women hope by speaking out about what happened to their siblings and pushing for changes in policing, the deaths of their loved ones won't have been in vain.

"Let's be transparent," Davis said. "Let's be honest. Let's start opening up conversations and treating children as they are humans, because they're treating our children like they're adults."

"With any human, if something is a little difficult or uncomfortable, we shy away from it, or we run the other direction," Findley said. "But right now, we need to face it head strong. Because I don't want to see another traumatizing video."

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from TODAY: