Congress rushed headlong into crisis mode Tuesday with a government shutdown days away, as House Speaker Kevin McCarthy faced an insurgency from hard-right Republicans eager to slash spending even if it meant halting pay for the military and curtailing federal services for millions of Americans.

There's no clear path ahead as lawmakers return with tensions high and options limited. On an evening vote, the House Republicans narrowly agreed to start debate on a package of bills to fund parts of the government. But it was a short-lived victory, because it's not at all clear that McCarthy has the support needed to actually pass the bills in the days ahead as holdouts demand steeper spending cuts.

“It's easy,” McCarthy quipped about how he planned to keep government from shutting down.

But with just five days to go before Saturday's deadline, there is no endgame in sight.

Trying to stave off a federal closure, the Senate pushed ahead with a bipartisan stopgap measure to keep offices funded temporarily, through Nov. 17, to buy time for Congress to finish its work.

The Senate advanced the bill late Tuesday on an overwhelmingly bipartisan vote, 77-19, though it still needs to go through a final vote. Then it would go to the House, where it would face a difficult path to passage.

The Senate bill would fund the government at current levels and include about $6 billion supplemental funding for Ukraine and $6 billion in U.S. disaster assistance that has been in jeopardy. It also includes an extension of Federal Aviation Administration provisions expiring Saturday.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer called the temporary measure from the Senate “a bridge towards cooperation and away from extremism.”

With a supportive nod, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell appeared on board with the bipartisan Senate plan saying, “Government shutdowns are bad news.”

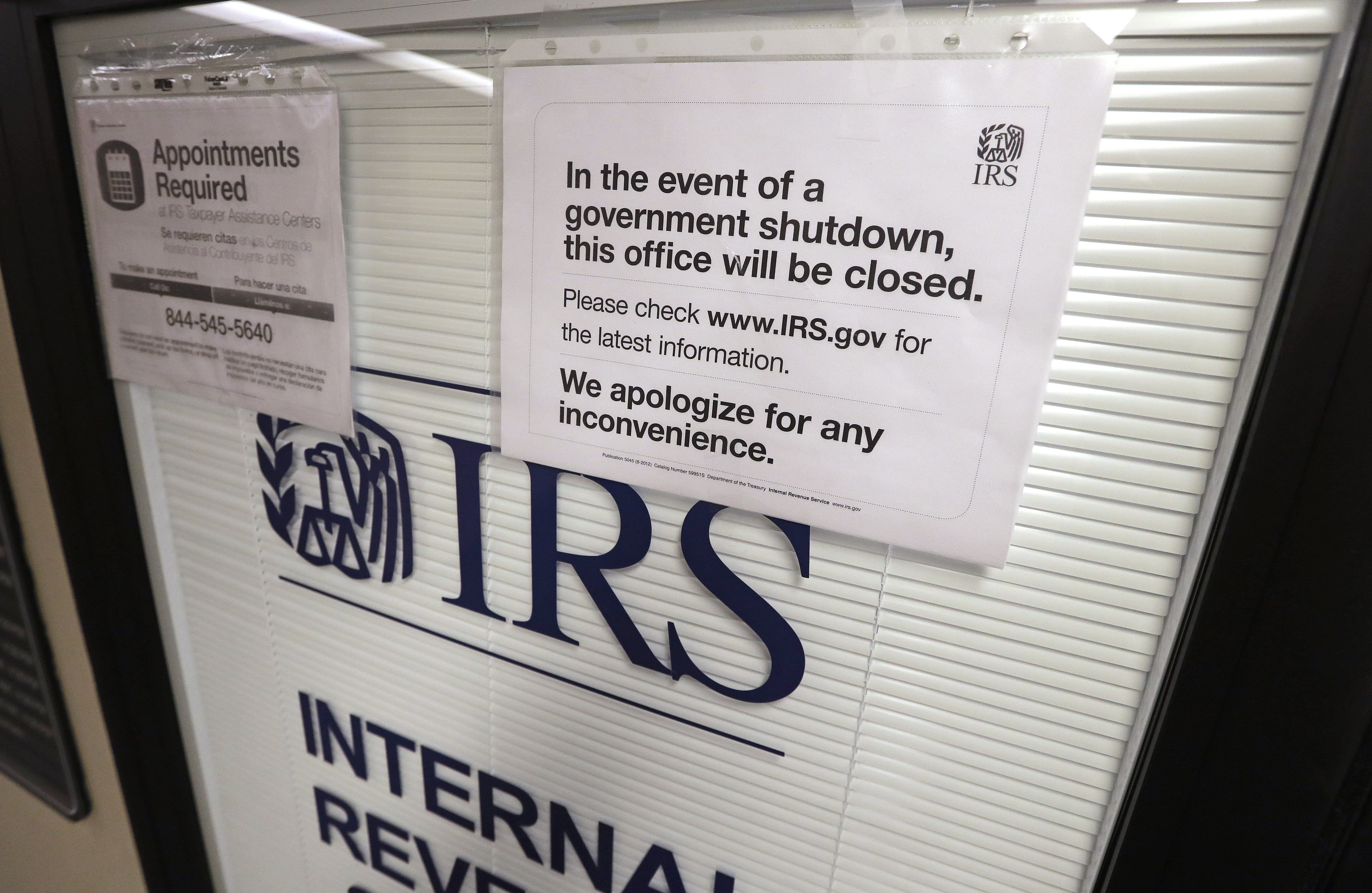

A government shutdown would disrupt the U.S. economy and the lives of millions of Americans who work for the government or rely on federal services — from the military personnel and air traffic controllers who would be asked to work without pay to some 7 million people in the Women, Infants and Children program, including half the babies born in the U.S., who could lose access to nutritional benefits, according to the White House.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

The standoff comes against the backdrop of the 2024 elections as a core group of hard-right Republicans are being egged on by Donald Trump, the Republican front-runner to challenge President Joe Biden. Trump has urged McCarthy's House to stand firm in the fight or “shut it down.”

It is setting up a split-screen later this week as House Republicans hold their first Biden impeachment inquiry hearing probing the business dealings of his son, Hunter Biden, as Congress spirals closer to a shutdown. It also comes as former Trump officials are floating their own plans to slash government and the federal workforce if the former president retakes the White House.

Against the mounting chaos, Biden warned the Republican conservatives off their hard-line tactics, saying funding the federal government is “one of the most basic fundamental responsibilities of Congress."

Biden implored the House Republicans not to renege on the debt deal he struck earlier this year with McCarthy, which set the federal government funding levels and was signed into law after approval by both the House and the Senate.

“We made a deal, we shook hands, and said this is what we’re going to do. Now, they’re reneging on the deal,” Biden said late Monday.

But Trump is pushing Republicans to dismantle the deal with Biden. “Unless you get everything, shut it down!” Trump wrote in all capital letters on social media. “It’s time Republicans learned how to fight!”

McCarthy brushed off Trump’s influence as just a negotiating tactic, even as far-right members keep torpedoing his plans.

He was hopeful the latest plan on a package of four bills, to fund Defense, Homeland Security, Agriculture, and State and Foreign Operations, would kickstart the process.

At the same time, McCarthy was also reviving his plan for the Republicans to pass their own stopgap measure even though a handful on the hard-right said they would never vote for it, denying him a majority. That proposal would fund the government while also adding severe border security provisions that Biden, Democrats and even some Republicans reject.

“I'm working all my time to make sure that there would not be a shutdown,” McCarthy insisted Tuesday.

But at least one top Trump ally, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., who is also close to McCarthy, said she would be a “hard no” on the vote Tuesday to open debate, known as the Rule, because the package of bills continues to provide at least $300 million for the war in Ukraine.

Other hard-right conservatives and allies of Trump may follow her lead.

While their numbers are just a handful, the hard-right Republican faction holds sway because the House majority is narrow and McCarthy needs almost every vote from his side for partisan bills without Democratic support.

The speaker has given the holdouts many of their demands, but it still has not been enough as they press for more — including gutting funding for Ukraine, which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy told Washington last week is vital to winning the war against Russia.

The hard-line Republicans want McCarthy to drop the deal he made with Biden and stick to earlier promises for spending cuts he made to them in January to win their votes for the speaker's gavel, citing the nation's rising debt load.

Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida, a key Trump ally leading the right flank, said on Fox News Channel that a shutdown is not optimal but “it's better than continuing on the current path that we are to America's financial ruin.”

Gaetz, who has also threatened to call a vote to oust McCarthy from his job, wants Congress to do what it rarely does anymore: debate and approve each of the 12 annual bills needed to fund the various departments of government — typically a process that takes weeks, if not months.

Even if the House is able to complete its work this week on some of those bills, which is highly uncertain, they would still need to be merged with similar legislation from the Senate, another lengthy process.