The word gymnastics is derived from the ancient Greek “gymnazein," meaning “to exercise naked.”

The sport, now among the Olympics’ most beloved events, was born millennia ago, as young men trained for war in the buff.

Throughout human history, in all corners of the globe, people have flipped and spun and twisted to explore the limits of the human body. Egyptian hieroglyphs depict backbends, according to Britannica, and stone engravings from ancient China illustrate acrobats.

In arenas today, gymnasts compete on a series of what are called apparatuses: both men and women do a tumbling routine, called a floor exercise, and launch themselves off a vault. But their other events are different. Men compete in a total of six: the floor, the vault, the pommel horse, still rings, parallel bars and horizontal bar. Women compete in just four, with the balance beam and uneven bars added to the floor and vault.

More Gymnastics Coverage

It wasn’t always that way. Early gymnastics included activities like rope climbing.

So how did gymnastics move from young Greeks training naked to specific, highly calibrated events with a complicated scoring system?

Why is it called pommel horse?

At the Games, men swing around a leather-covered block with handles called a pommel horse, that in early iterations roughly mimicked the size and shape of the actual animal. Alexander the Great, king of Macedonia from 336 to 323 B.C., had his Macedonian soldiers train on a similar device to practice mounting their horses for battle, according to the European Gymnastics Service.

The modern version was invented in the early 19th century by German Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, known as the “father of gymnastics” for founding a series of gymnastics centers meant to cultivate health and patriotism. These gyms were meant, in part, to get young Germans ready to defend the country against Napoleon’s French military.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

Jahn also invented the early versions of the bar exercises that exist today: parallel bars and horizontal bars for men, and the women’s uneven bars evolved from the parallel bars to showcase agility and elegance.

How did the vault in gymnastics start?

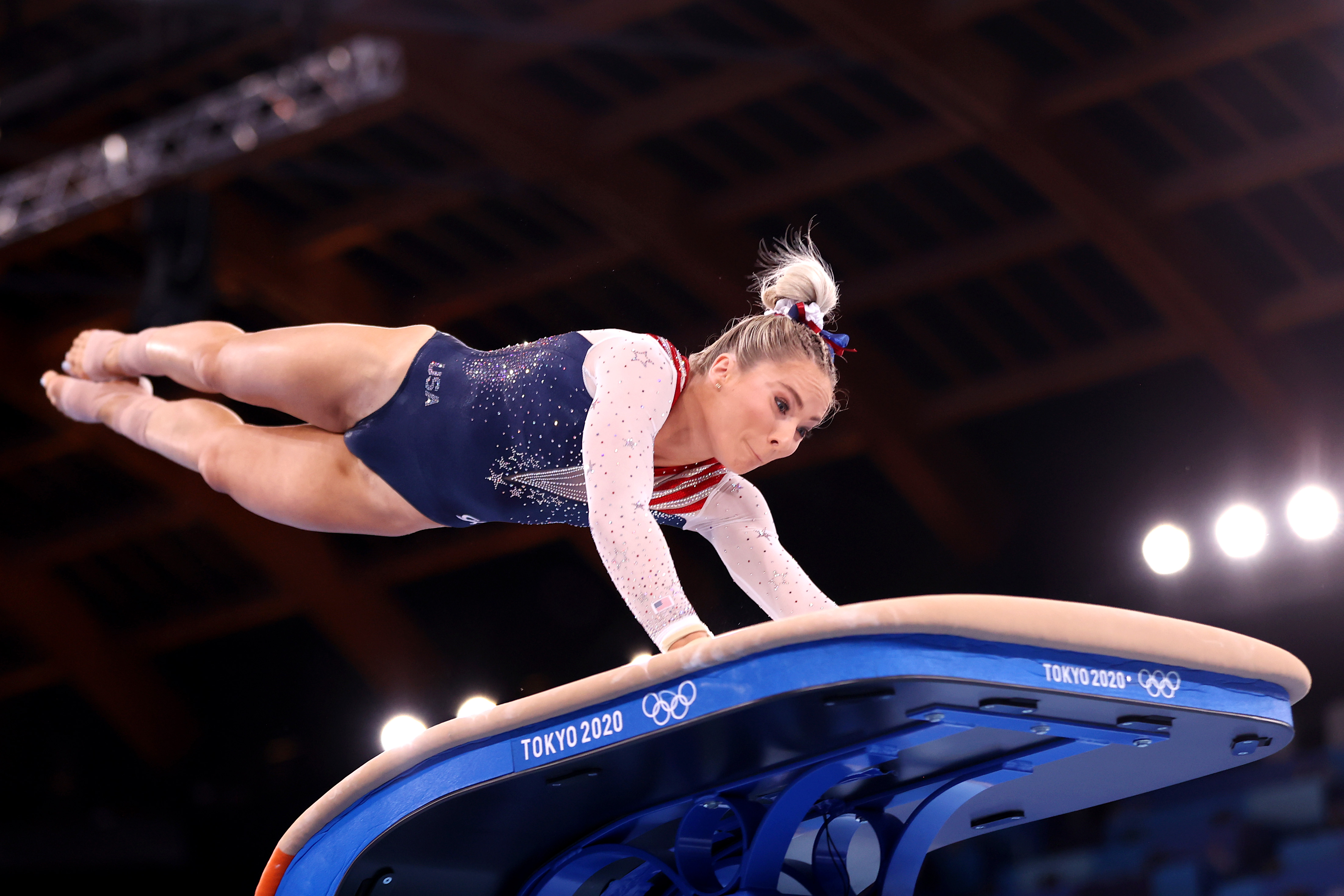

For most of modern gymnastics history, the vault looked like the pommel horse without handles. Both men and women sprint toward it, flip and launch themselves into a series of spins and twists.

But it was redesigned two decades ago after horrific injuries in the 1980s and 1990s as gymnasts started trying more risky maneuvers: American Julissa Gomez was paralyzed in a vaulting accident in 1988 and died three years later. A decade later, Chinese gymnast Sang Lan fell, broke her neck and was paralyzed.

Then, in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, the vault was set two inches too low. In this sport of precision and timing, the problem caused a disastrous set of mistakes including one athletes nearly missing the vault entirely.

The new apparatus was called a “vaulting table,” and has a wider, more cushioned surface for athletes to spring from. Slate magazine reported in 2004 when it made its first Olympics debut that athletes had taken to calling it “the tongue.”

Why are they called still rings in gymnastics?

When men suspend themselves on two rings, hanging from straps, they are performing the gymnastics event that requires the most physical strength of any of the apparatuses.

They are called still rings because the gymnasts attempt to keep them as stationary as possible as they swing into different positions. They were originally called the “Roman rings,” because their origin as a strength-training device is believed to date back thousand of years in Italy. In early iterations of the modern Olympics, they were sometimes referred to as the “flying rings.”

Where did the balance beam come from?

The balance beam started off hundreds of years ago as a log suspended in the air. It has been refined over the years to a padded beam, 16 feet long, four feet high and four inches wide.

It is considered the women’s event that requires the more focus and precision. A minuscule misstep can send a gymnast tumbling to the ground.

AP National Writer Claire Galofaro is on assignment in Tokyo covering gymnastics at the Olympics.