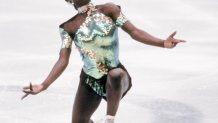

Surya Bonaly didn’t have any local role models who looked like her when she embarked on an ice skating career in the early 1990s while growing up in France.

As a Black girl who was adopted from an orphanage in Nice by white parents, she would often look around the rink and realize she was the only skater of color at many events in Europe.

“I wish there was somebody back in my day who was able to do that for me,” Bonaly told TODAY. “You always need someone to be the first to do something. I didn’t have that, so in my case, I had to be the one for Europe.”

Thirty years ahead of her time

Not only was Bonaly, 48, a Black pioneer in a predominantly white sport, she also was ahead of her time on the ice when it came to the explosive athleticism that’s now a requirement to reach the top of the sport.

At the 1992 Olympics in Albertville, France, Bonaly became the first woman ever to attempt a quadruple jump in Olympic figure skating when she landed a four-revolution jump. It did not count for the scoring because she was ruled to have under-rotated it, but it showed the possibilities for a sport where grace and artistry often overshadowed athleticism.

It took 30 years for a woman to finally land another quad jump in the free skate at the Olympics when a host of them did so in Beijing this month, including gold medalist Anna Shcherbakova of the Russian Olympic Committee. She landed a pair of quad jumps as part of her winning free skate routine on Thursday, while her ROC teammate, Alexandra Trusova, landed five quad jumps of her own to take the silver.

The performances in Beijing are the culmination of what Bonaly started decades ago.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly> Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

“It’s amazing to think it took that long for it to happen at the Olympics, that it was 30 years ago that I was really pushing myself to go forward,” Bonaly said.

It was that inner fire that led Bonaly to become a five-time European champion and a three-time silver medalist at the World Championships. It’s also what led her to give everything to a sport that didn’t always love her back, whether it was judges evaluating her performances, commentators referring to her with racially coded words like “exotic,” or competitors who didn’t know what to make of the Black skater in colorful costumes.

While many casual fans know Bonaly for the stunning backflip she pulled off at the 1998 Olympics that remains a YouTube staple, it’s her perseverance in the face of adversity during her career that has only grown more memorable with each generation.

Andrea Jordan, the chief operating officer of Figure Skating in Harlem, has made sure her young skaters of color know all about Bonaly, who has also met with them in person. In a month not only celebrating the Olympics but also Black history, Bonaly's legacy stands out.

“Being an athletic woman of color, but also in many ways being judged because of her physical appearance and her characteristics in a way that was unfair, to be able to break through all of those barriers and still persist in that spot and accomplish all what she accomplished is remarkable,” Jordan told TODAY.

“For us, as I think about her meaning to our skaters, representation matters. Young people need to see individuals that look like them on and off the ice.”

Starting from scratch

Bonaly tried a host of sports as a child thanks to her mother, Suzanne, who had her competing in fencing, ballet, diving, gymnastics and figure skating. Her gymnastics background ended up playing an important role in the acrobatic feats she would one day pull off on the ice.

The only other prominent Black skater in singles competition at the time was American Debi Thomas, who won bronze at the 1988 Olympics. Bonaly admired Thomas as a fellow Black woman in the sport but particularly looked up to Midori Ito. The 4-foot-9 Japanese dynamo was compact, explosive and muscular, able to land seven triple jumps during her free skate at the 1988 Olympics.

“I would watch videos over and over of her, repeating her program every practice like her,” Bonaly said. “She was an amazing jumper. Asian skaters were not very common at that time, and Midori Ito does not have that typical (figure skating) body of being super slim.

“She was very muscular and like a bomb on the ice, and she inspired me to believe I could be like her. She helped people kind of start getting used to seeing people of color skating at a high level.”

Bonaly quickly became a star in France, winning the first of her nine national titles as a 15-year-old in 1989 while working on her quad jump. She was determined to hone the difficult maneuver, suffering through painful falls in practice during a time when there weren’t cutting-edge recovery therapies like there are now.

However, her drive to push the boundaries of the sport with her dazzling jumps and colorful costumes soon clashed with a figure skating culture and judges who prized thin, graceful skaters in muted dresses.

Frustration on the big stage

At the 1992 Olympics, she argued with her coach in practice about whether to attempt a quad jump in her free skate routine. He advised against it with an eye on how it might be judged, but she went for it anyway because there was always one group whose approval she wanted the most: the crowd.

“I didn’t think about politics and judges,” she said. “It was not my field. I just wanted to get people clapping and out of their seat and put on a show.”

Bonaly didn’t quite land it and ended up taking fifth, but she made an impression at an Olympics that featured some of the biggest names in figure skating history — Kristi Yamaguchi, Midori Ito, Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding.

At the 1993 World Championships, she landed seven triple jumps with a triple combination, while Ukrainian skater Oksana Baiul landed five triple jumps with no combinations, yet Baiul won the gold.

“It was a challenge of being the best and being better than the champion, who was white,” Bonaly said. “I had to be better than a normal skater. It was a challenge every single day, but in a way, it was just like a real fun goal to reach every night.”

Bonaly took fourth at the 1994 Olympics behind Baiul, Kerrigan and Chen Lu, but her biggest disappointment came later that year at the World Championships. She had worked to improve her gracefulness while even cutting her ponytail in order to be more appealing to the judges. It wasn’t enough, as she finished second behind Japan’s Yuka Sato after skating a rigorous program.

During the medal ceremony, she took off her silver medal in frustration. Tears flowed down her face as she stood still on the podium while the other two skaters waved to the crowd.

Figure skating coach Joel Savary, 37, the author of “Why Black and Brown Kids Don’t Ice Skate” and the founder of the Diversify Ice Foundation, remembers watching that emotional moment as a young boy. Bonaly was booed by the crowd and then immediately rushed by reporters thrusting microphones into her face and asking if she was going to give up the sport.

“I feel that was the beginning of the judges really wearing her down through this sort of attrition of not giving her what she truly deserved,” Savary told TODAY. “The feeling that I felt was it paints another negative picture of a person of color. You oftentimes think of it as the angry Black woman stereotype, but honestly, that was the only voice that she really had to share that this was unfair.

“I think she did what she believed was right, and I think a lot of people of color automatically were just saying, ‘This sport is unfair, I’m not going to have anything to do with it.’”

Savary believes that moment had a ripple effect.

“People watched her and turned to another sport and said, ‘I’m going to track and field, where the person who makes it to the finish line first wins, or basketball, where the team that scores the most points wins, not this subjective sport,'" he said. "I think people of color saw that and gravitated to more objective sports as opposed to figure skating, with that subjective artistic merit being such a huge part of it.”

As for Bonaly, she looks back on it with decades of perspective as a moment she does not want to define her.

“I didn’t want any excuses,” she said. “I didn’t want it to be that I didn’t win because people are racist or people don’t like me. If I didn’t win or finish at the top, I probably didn’t do enough. My only goal was I need to do more than anyone else.”

Bonaly made one last statement at her final Olympics in 1998 when she stunned the crowd in Nagano with a backflip, even though backflips had been banned from competition. She had ruptured her Achilles tendon ahead of the Olympics and could not complete her planned routine, so she went for a show-stopping move that became the talk of the Olympics despite Bonaly finishing in 10th place.

“They outlawed the backflip, saying that when she did it, she landed on both feet, and for jumping, the judging says you should land on one foot,” Olympic historian Bill Mallon told TODAY. “Bonaly actually a couple times landed on one foot just to make a statement, which is incredible just to be able to do that.”

Her relentless push for bigger and more acrobatic jumps also planted a tiny seed that led to changes in the way the sport is judged. The point system officially changed after a judging scandal marred the pairs final at the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City.

“The judging has changed so that it’s much more based on athleticism and jumping now,” Mallon said.

Bonaly didn’t think much of the backflip at first because she did it all the time in practice, but she admittedly has watched some of the old highlights with pride.

“You’re somewhat confident as an athlete, but I was reserved back then, almost like I underestimated myself,” she said. “Now I watch some videos of some of my programs on YouTube, and I’m like, ‘That program was the bomb!’”

A career over family

Figure skating remains central to Bonaly’s life, as she lives in Las Vegas and works as a coach for skaters ranging from 5 to 18.

She skated professionally for years on the Champions on Ice tour, showing off her backflip to roaring crowds before retiring in 2015 to coach full time. Her partner, Peter Biver, is also a skating coach, but she said her dedication to the sport cost her an opportunity to have a family.

“I missed the train,” she said about not having children. “I knew for me if I stop for nine months of skating, maybe I won’t be able to get my next contract. I couldn’t just take a break because I was so afraid to lose everything.”

Bonaly also is a motivational speaker and the subject of a new children’s book called “Fearless Heart,” an illustrated look at her journey that she wrote with author Frank Murphy. The cover features an illustration of Bonaly in the middle of her signature backflip.

Where is the next Surya Bonaly?

In the decades since their peak, skaters like Bonaly and Thomas have looked more like outliers than signifiers of the next generation of Black skaters. There were none on this year’s U.S. team that competed in Beijing.

The last African American skater in the Olympics was in 2006, and no skater of African descent has won an Olympic medal in the singles competition since Thomas in 1988. Germany’s Robin Szolkowy won bronze in the pairs competition in 2010 and 2014.

“It’s true that figure skating can push you away because it’s an expensive sport,” Bonaly said. “Especially in America, it’s very expensive where you have to pay for your own private lessons.”

Organizations like Diversify on Ice and Figure Skating in Harlem work to expose young children of color to the sport, push down the barriers for entry and raise funding to help them train. Savary said it can cost as much as $50,000 a year to reach an elite level.

“Cost still remains a huge issue, and you look at the return on investment for a skater,” Savary said. “You can put in all this money and still be judged unfairly and have nothing to show for it. A lot of kids quit skating whose families are not super-rich and are in incredible debt and taking out second mortgages to pay for all of it.”

Savary believes the latest generation can take a cue from Bonaly, who had plenty of barriers of her own but didn’t let it stop her.

“I think we need to continue understanding our history in the sport, but also looking at how strong someone is like Surya,” he said. “If she can do this, we can all push through a lot harder.”

She embodies what Jordan is trying to teach at Figure Skating in Harlem.

“We have a creed in our curriculum for our students, and part of it is, ‘I am the dreams of women past, and I’m the hope of those to come,’” Jordan said.

“For me, that is what Surya represents — all of the dreams that we’ve had as girls of color that she manifested on the ice, but also the hope of those dreams our girls coming up are going to realize because of trailblazers like her.”

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from TODAY: