One Chicago community advocate remembers West Woodlawn as it was in the 1950s and 60s - a vibrant and bustling community.

Siri Hibbler, the CEO of the Garfield Park Chamber of Commerce, paints a similar picture of 1970s East Garfield Park.

“We had we had bowling alleys, skating rinks,” she said. “Everything that a kid wanted to do, they could do in Garfield Park, they could do on the West Side of Chicago.”

Now, both communities see many vacant lots.

But what happened?

Some point to the 1968 Chicago riots following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and that wasn’t the only reason.

The closing of factories like Brach’s and Western Electric meant the loss of middle-class jobs.

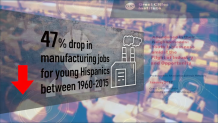

A 2017 report by the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute found a 26% drop in manufacturing jobs for young African Americans and a 47% loss among young Hispanics between 1960 and 2015.

Then, there were government policies, like the demolition of abandoned buildings, which was embraced by some neighbors.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly> Chicago Catch-Up newsletter.

Local

“It becomes a haven for the gangs and the drugs and the homeless, the prostitution, and at a certain point, it overwhelms the neighborhood,” one resident said in 2012.

Since 2008, the city of Chicago has demolished more than 5,300 homes, according to the Department of Buildings. When contacted by NBC 5, a spokesperson wouldn’t speculate on how many vacant lots exist in the city today.

The demolition that left vacant lots was presented as a way to bring peace to struggling neighborhoods, but some say it has had the unintended consequence of stifling economic development.

“So people that have come to me and said, I want to come to Garfield Park, they see the challenges,” Hibbler said. I want to come to the West Side, but there's nowhere to put a business because they're all vacant lots.”

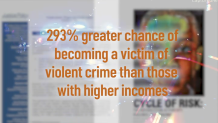

No new businesses in the neighborhood means no additional jobs, and multiple studies have revealed that fewer jobs can lead to more crime.

According to the Justice Policy Institute and Heartland Alliance, one-third of people in U.S. jails said they were unemployed when arrested, and people living in poverty have a 293% greater chance of becoming a victim of violent crime than those with higher incomes.

Anti-violence activist Eddie Bocanegra says those people are key to making communities safer.

“If you’re able to engage individuals and you expose them to something different, you allow them to be part of the solution,” he said.